Sir Francis Drake

Art vs. History at the University of California

One of the older and more outstanding architectural features of the venerable and respected School of Medicine of the University of California at San Francisco is beautiful and intimate Toland Hall, a small half-round room with curves of steeply tiered seats, a dramatic radial array of ceiling beams, interesting overhead window-lights and, on the walls behind the upper arc of seats, a set of colorful and detailed murals depicting, it is said, the history of medicine in California. This charming amphitheater, tucked away in a huge, labyrinthian and otherwise starkly ugly building erected in 1917, is a reminder of Dr. Hugh Toland, a gold-rush era physician who founded the first school of medicine in San Francisco, and of the long-gone original Toland Hall he donated to the fledgling university.

The murals gracing the walls of the present Toland Hall were painted from 1937 to 1939 by the late artist Bernard Zakhiem, who is often associated with the great muralist Diego Rivera. The hall is still in constant use today and the murals thus have played a graphic role in conveying history to several generations of medical professionals. Additionally, the hall is often used by non-medical groups, for it is an excellent little theater and is also ideal for seminars and such; a childrens' summer day-camp presents performances there as does a UCSF thespian troupe. So, it is safe to say that over the years many thousands of people have gazed upon California history as presented by the University of California through Mr. Zakhiem's murals.

Apparently there was a bit of a dust-up when the murals were first unveiled. It seems that some faculty members might have been less than happy about the introduction of such a colorful potential distraction to the serious business of educating future doctors. (One also wonders if some conservative political sensibilities might have been offended by the similarity of style (albeit not of content) of the murals with Rivera's distinctly left-leaning works.) The controversy resulted in the private 1939 publication, in an edition of 1,000, by an anonymous person who was "interested in staff and student response to the project," of a 24-page illustrated booklet describing the murals in detail and, in general, extolling their virtues. The dust settled and the murals stayed, only to fall victim to the cold-war hysteria of the late 1940s when they were slapped over with wallpaper and paint. Fortunately this shameful crust wasn't much tougher than the cowards who applied it and in 1962 the gunk was stripped off and, once enough money was raised, the murals were restored to their former glory.

The most recent published notice of the murals seems to be in (and on the cover of) the fall, 1996 issue of the Bulletin of the Alumni-Faculty Association of the UCSF School of Medicine. The lead article, by Dr. Robert A. Schindler, is devoted to these works. Dr. Schindler, after expressing appropriate outrage at the indignities described above, writes:

"One of the wonderful things about history is that we have the opportunity of distance. No longer is the issue of whether the murals were leftist of rightist important. It is their artistic merit and the historic story they portray that is important."

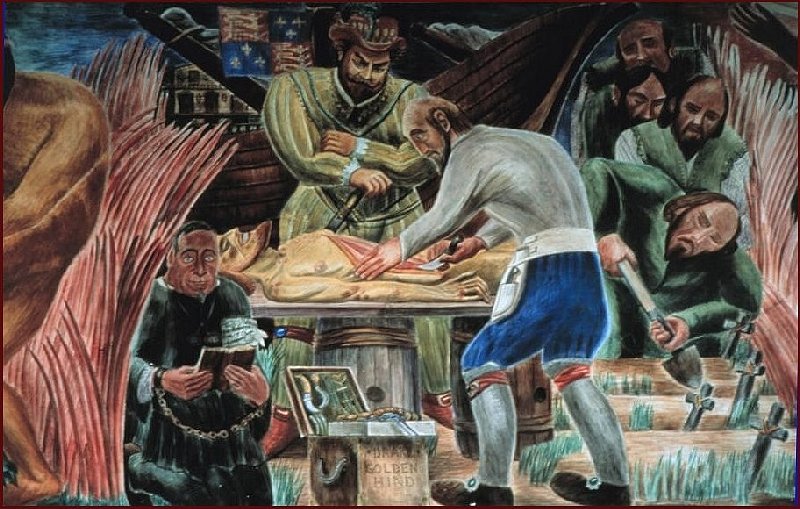

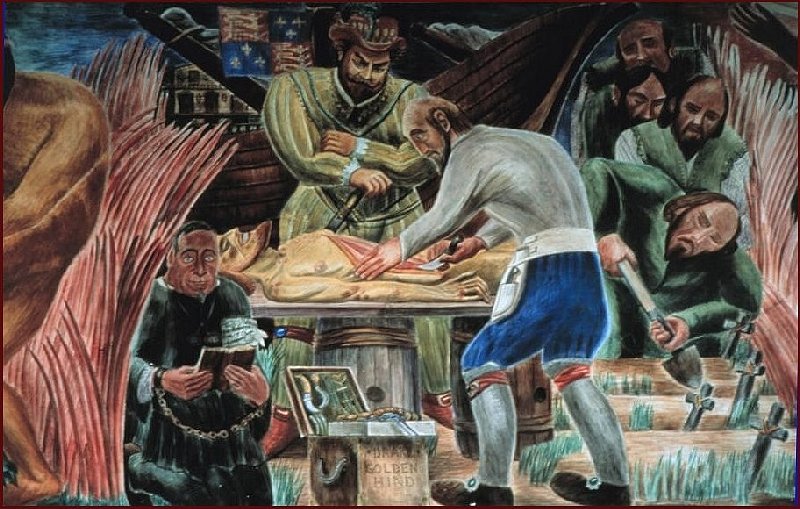

Indeed. There is, however a little problem (and this finally brings us around to the subject of this web site - Francis Drake). One of the murals shows a rather grisly scene:

the 1939 dissertation on the murals describes the above as:

"...an episode from the career of Sir Francis Drake, who landed near San Francisco Bay in 1579, and claimed the land for England. With his back to his ship he grimly supervises an autopsy which the ship's surgeon is performing upon Drake's younger brother, thus proving his death due to natural causes rather than to the vengeance of a wrathful deity. To the right four sailors finish burying those of their comrades who perished of the same disease, while to the left the chaplain, prayer book in hand but manacled, and wearing a humiliation badge, suffers the displeasure of the Captain for spreading superstition among the crew."

Fifty-seven years later, in the 1996 article, Dr. Schindler describes the scene in similar fashion:

"An interesting vignette displayed on the back panel is that of Sir Francis Drake, who came to California in 1579 and took possession of it for Queen Elizabeth I of England. His younger brother died in California, and this panel illustrates the post-mortem examination by the ship's surgeon determining that his brother died of natural causes."

Both of these commentaries are accompanied by photographs of the relevant part of the murals. The problem? None of it happened. Drake's brother died during an earlier voyage to the Carribean and as far as is known no one in Drake's party had so much as a case of sniffles, let alone died, in California. Thus there was no California autopsy and there were no California burials. This was a good thing, because there was no ship's surgeon to investigate the non-deaths - he having been killed long before in Patagonia. Finally, there was no chastisement of Chaplain Fletcher in California; that incident took place much later, in the Western Pacific and had nothing to do with either disease or superstition.

So, in the course of fifty-seven years, on the grounds of the largest educational institution on the West Coast, in the city in which more attention has been focused on Francis Drake in California than in any other place and during two episodes of intense scrutiny by members of the academic community, not one word seems to have surfaced about the utterly fictional nature of this insertion into the extensively detailed and otherwise historically accurate murals.

It is this surrounding accuracy of the rest of the murals that makes the Drake fiction particulary dangerous, because there is nothing to make an observer who is knowledgeable about modern medical history suspicious. The result is that such mythology can easily become embedded in subsequent literature, where it is blandly reported as fact. For example, in the library of the University of California can be found a book titled A History of American Pathology by E.S.Long, M.D., Ph.D. (Thomas Books: NY, 1962) in which is stated, in an endnote on page 394,

"One of Francis Drake's surgeons, James Wood, was ordered to perform an autopsy on the body of Sir Francis' brother Joseph, who died at a California port in a febrile epidemic ..."

It seems unlikely that artist Zakhiem invented this "history," and it can be supposed that he must have had someone advising him on the myriad details of the murals. Where this twisted image of Drake's California history originated remains a mystery, and is the subject of an ongoing investigation by the present writer. In any event, it serves as yet another example of how absolutely nothing concerning Francis Drake's great journey around the world, no matter what credentials the source might present or how authoritative the words might sound, can safely be taken at face value.

Many thanks to Dr. Walter Finkbeiner, who brought this interesting matter to my attention. In the course of researching the history of early autopsies, Dr. Finkbeiner, a University of California pathologist, noticed discrepancies between the murals and written accounts of Drake's career. His investigation led to me through this web site; I was able to confirm his suspicions, and he subsequently made available to me the material cited above.

Nova Albion Research

Copyright 1998 by Oliver Seeler

Please feel free to send your comments

to oseeler@mcn.org

Return to the main Drake page...